19th May 2020

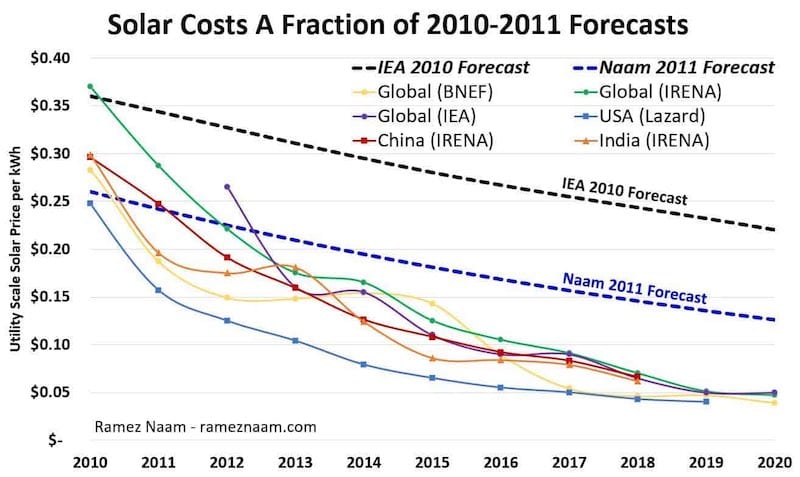

Clean technology advocate and futurist Ramez Naam admits he was wrong about the price of solar. His forecasts in 2011 were among the most optimistic in the world, but he turned out to be wrong by at least a factor of two.

Solar is now half the price he predicted nearly a decade ago, and already at a price that established institutions like the International Energy Agency thought wouldn’t be possible for a century to come. That’s how dramatic the cost of the technology has fallen. And it’s going to get cheaper.

“Solar has plunged in price faster than anyone – including me – predicted. And modeling of that price decline leads me to forecast that solar will continue to drop in price faster than I’ve previously expected, and will ultimately reach prices lower than virtually anyone expects. Prices that are, by any stretch of the measure, insanely, world-changingly cheap.”

We saw this in action last month, when Abu Dhabi Power Corporation’s 2GW Al Dhafra project attracted record low bids of 1.35 cents in US currency, roughly $A0.02/kWh, or $A20/MWh, from a consortium including French energy giant EDF and Chinese solar company JinkoPower.

That bid promises to deliver a levelised cost of solar energy at almost half the once record-breaking price achieved three years ago for the mammoth 1.17 GW Noor Abu Dhabi solar park, which started sending power to the grid mid-way through last year.

As Naam explains in this must-read blog post, solar has got to this point largely through sheer scale of global deployment.

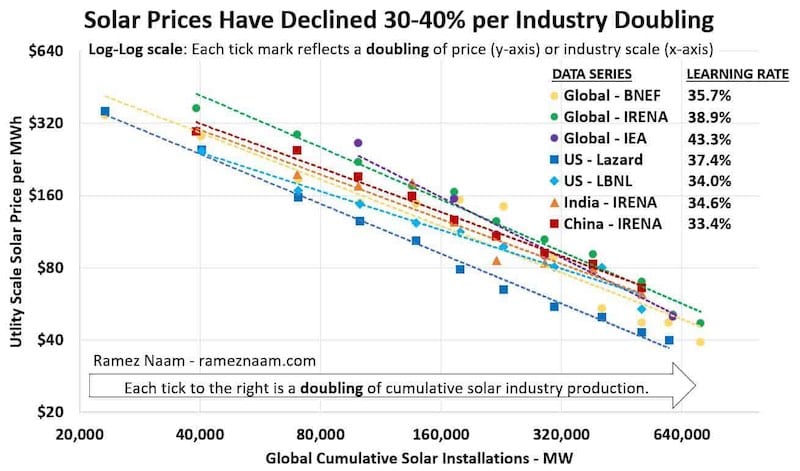

He uses data from seven different sources spanning global, US, Chinese, and Indian trends, to paint “an incredible picture” that shows the price of solar electricity from utility-scale systems dropping by anywhere between 30-40% with each doubling of cumulative solar deployment.

“This is a stunning pace of decline. It’s far higher than the bulk of academic studies and industry projections, which typically fall into the 10-20% learning per doubling range,” Naam says. “And it’s more than twice the 16% learning rate I found in my 2015 analysis.”

But perhaps even more incredible is that this learning curve is by no means done. The world is headed from insanely cheap solar, to ultra-cheap solar.

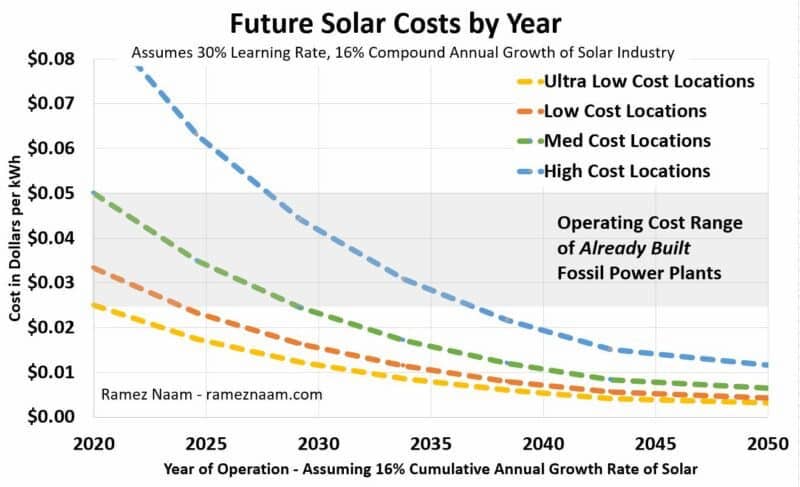

Naam says the world is currently entering what he calls “the third phase of clean energy,” where building new solar and wind power is cheaper, eve, than keeping existing fossil fuel plants running.

And cheap solar will be a major part of this.

“With average prices in sunny parts of the world down to a penny or two by 2030 or 2035 …building new solar would routinely be cheaper than operating already built fossil fuel plants, even in the world of ultra-cheap natural gas we live in now,” Naam writes.

He comes to this conclusion using what he describes as a “cautious” learning rate of 30 per cent. As illustrated in the chart below, just two more doublings of scale, to 2,400GW of solar producing roughly 8% of global electricity demand, would see solar costs cut in half from today’s levels.

“In the sunny parts of the world with low costs of capital, labor, and land, we could routinely be seeing unsubsidized solar in the 1-2 cent (US$) range. In California (typical of the green line) we could be seeing unsubsidised solar at 2.5 cents per kwh. In northern Europe, we could be seeing utility scale solar routinely priced at 4-5 US cents per kwh,” he writes.

Naam notes that to the far right of the graph, solar deployment hits 19 Terawatts. “This may seem like an absurd, pathological amount of solar, enough to provide 2/3 of the world’s current electricity production,” he says, but when you consider the changing shape of electricity demand and supply, it’s not so implausible.

Naam argues that this sort of terrawatt-scale demand for cheap and abundant solar power will come from a richer world; a world that has shifted to electric transport; grids dominated by flexible demand; the arrival of cheap energy storage, and finally; industrial decarbonisation.

“Add these up, and it’s plausible that solar’s contribution to the energy system could double or triple the amount currently considered feasible for solar to provide,” he says.

But while solar might give the appearance of a self-powered juggernaut on a set course to solve the world’s energy problems, it is not. As Naam himself stresses, “projections are only projections” and we shouldn’t “blindly assume” that they will come to pass. As usual, policy will be key. And as usual, that is a concern for Australia.

“There will be real obstacles – technical, economic, social, regulatory, and political – that will all need to be overcome to bring this to bear,” Naam says.

“And there may well be a physical floor price that solar reaches as prices drop too close to the cost of land and other resources that are resistant to cost decline.”

Other technologies – in particular various forms of energy storage – will also have to keep up the pace. And, to be sure, when Naam published a Twitter version of his thoughts it sparked an interesting reaction from others pointing out the need for storage, or advanced demand management. But the costs of those are coming down too.

Even so, says Naam, “the incredible pace of solar provides us an incredible tool for decarbonising our electrical grid, while ultimately lowering costs for consumers, businesses, and industries.

“And for now, have hope. Technology innovation – initially kicked off by farsighted policy – is giving us better and better tools to decarbonise society, while reducing the cost of energy, and increasing global prosperity.”

Someone should tell the Australian government.