20th January 2015

So, who wants to be an energy pro-sumer? In some states in Australia, around one in four houses already boast rooftop solar PV systems, and it’s having a big impact on the operation and the optics of the National Electricity Market, with big implications for the traditional business models of generators, retailers and network operators alike.

The next big question is by how much this penetration will increase, and to what extent will it be accompanied by battery storage? The anecdotal evidence suggests there is a lot of inquiry about storage from consumers and grid operators. But where will the the best value proposition lie – in the household, or in the grid? And who is going to deliver this service?

First of all, however, let’s understand the reasons why Australian households might want battery storage in the first place.

Mostly, it is due to the fact that households are not getting paid for exports of solar electricity back into the grid. In NSW and parts of Queensland, any payments are voluntary. Even where retailers are offering 5.1c/kWw, they are then selling those same electrons to the solar household’s neighbour for as much as 48c/kWh if that household in on peak rates. Someone is making money, and it’s not the solar households.

Gordon Weiss, a solar and storage expert from Sydney-based Energetics, produced some interesting graphs and observations at the Clean Energy Week event last week.

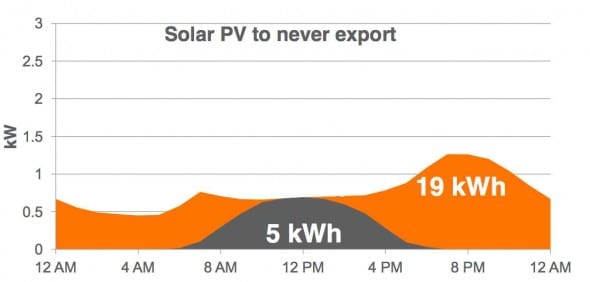

He said that to limit a solar system to have no exports – based on average daily household consumption of 19kWh, the array would have to be sized at just 600 watts – just two or three panels. It would look something like this.

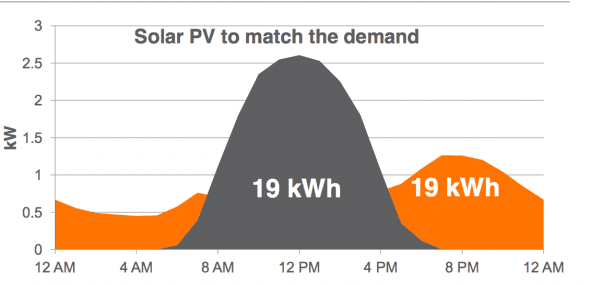

A larger system of around 2.5kW (see graph below) – of about 8-10 modules – results in a huge amount of exports during the middle of the day. Some things can be done to address that – timing appliances to operate during that period, for instance – but the most effective option is to find a way to store the energy, to put it in a box for use later in the day or the evening.

Let’s also remember that the average system size installed in NSW when those generous gross feed-in tariffs of 66c/kWh were on offer was 3kW. Since then, the average system has increased to nearly 4kW. When those NSW systems come off those tariffs at the end of 2016, there will be some 160,000 households wondering how best to leverage the value of their output.

Here are a few simple rules that Weiss has on the attraction of rooftop solar and battery storage.

Rooftop solar: When the levellised cost of solar PV falls below the sum of the wholesale price and retail margins, then it doesn’t matter what happens to network tariffs – even if they went negative! This is similar to what we said a few weeks ago when we pointed out that even if the cost of coal fired generation was free, it could not compete with solar. The price of wholesale and retail margins is 13c/kWh. In the sunniest states, rooftop solar is not so far from that.

Battery storage: Weiss says that when the levelised cost of solar PV plus battery storage falls below the evening peak price, then batteries will appear in garages and basements.

Off-grid: And when the levellised cost of solar PV and batteries falls below the average cost of power to the consumer, then consumers will go off-grid. Of course, networks will have ways of repackaging tariffs and moving away from volumetric rates, adding in fixed components and capacity tariffs, but it seems unlikely that they will be able to bring the average bill down below $2,000 a year. That is the key benchmark for solar and storage (and back-up – which is another problematic issue if this happens en masse).

Of course, it’s not quite as simple as that – but that is the basic maths that households are facing. Once again, we are brought back to the fact that it is up to the utilities – be they network providers or retailers – to tailor their product to match the cost options being presented by the new technologies. It is not good enough to simply repackage tariffs to make solar and storage more expensive, as networks are inclined to do, and as we reported yesterday.

It seems inevitable that regional communities will look to evolve in some form of micro-grid arrangement, using locally generated energy and local storage. Network operators in South Australia, Western Australia and Queensland accept this as inevitable. The NSW government is promoting the search for the first town inthat state that could do the same and become the first zero net energy town.

The difficulty comes in how to manage the issue in the cities.

On Weiss’ rough numbers, to take an average household off grid would need a 7kW solar system, around 35kWh of storage, plus a generator of some sort. That is not what you want to see happen in huge numbers in the suburbs.

As Weiss says: “Do we want, as a society, lots of 35kwh battery storage systems in the suburbs and lots of backup generators? Maybe a better solution is centralised storage – a big battery pack next to sub stations.”

But that requires the network operators to get cracking, and to do this at a competitive price.

“Right now, the pricing signals that are going out to consumers may result in people going off grid in metro areas in large numbers. That wont be environmentally or economically desirable,” says Weiss.

“We have to acknowledge the reality of new technologies. We have to begin to think of he grid as fundamentally different thing. It’s no longer here to deliver centralized energy to consumers, but to ciruculate energy. Solar PV with storage is now part of the landscape. The challenge is to use it efficiently.”

And just how far away are the economics of solar and storage?

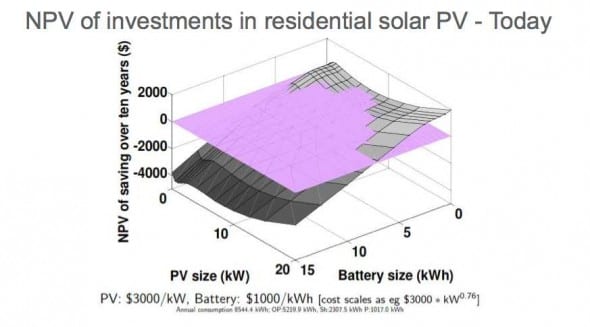

Weiss pointed us to these fascinating graphs, produced by the University of Sydney this month as part of a report being prepared with the CSIRO.

They might give you a bit of a headache at first glance, but allow me to explain.

In the first graph, the purple line is zero NPV (net present value) – and to the right is a rising grey colour, illustrating that smaller to medium size solar PV systems, with no storage, offer some positive returns in the current market. Those figures are based on $3,000/kW solar PV and $1,000/kWh battery storage costs.

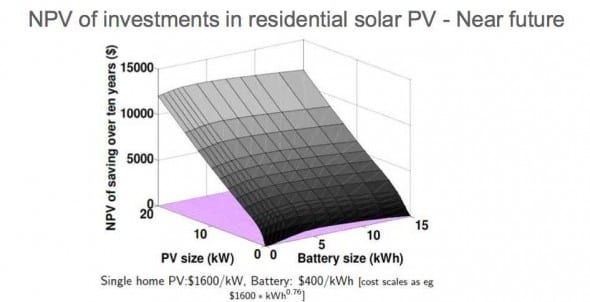

Hop to the second graph, which is based on $1,600/kW solar PV – some say that already exists, but be careful about the quality – and $400/kWh battery storage.

On that basis, it is a bit of a no-brainer. The NPV increases sharply, and does so by the same margin when large battery storage systems are installed. That is more than $10,000 of savings over 10 years with large solar and storage systems.

Hence, Weiss’ conclusion that we could see homes with very large arrays and very large battery storage systems in the suburbs. Hence the need for utilities to get on the front foot – and not just by twisting tariffs. This is going to be one of the big social equity issues of the day.